|

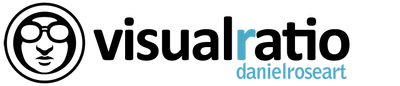

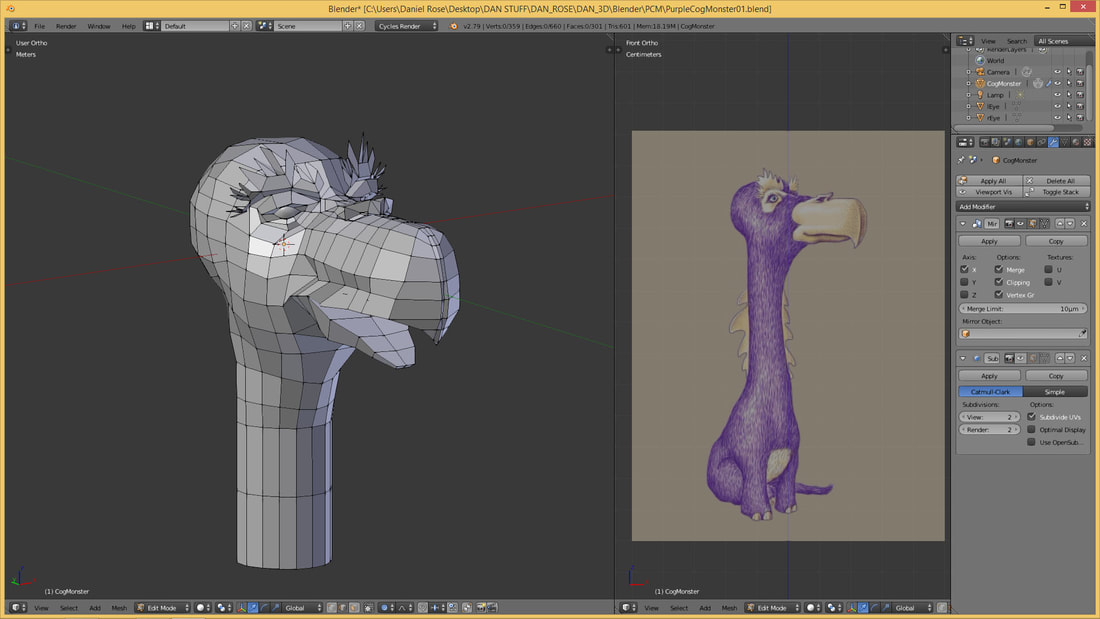

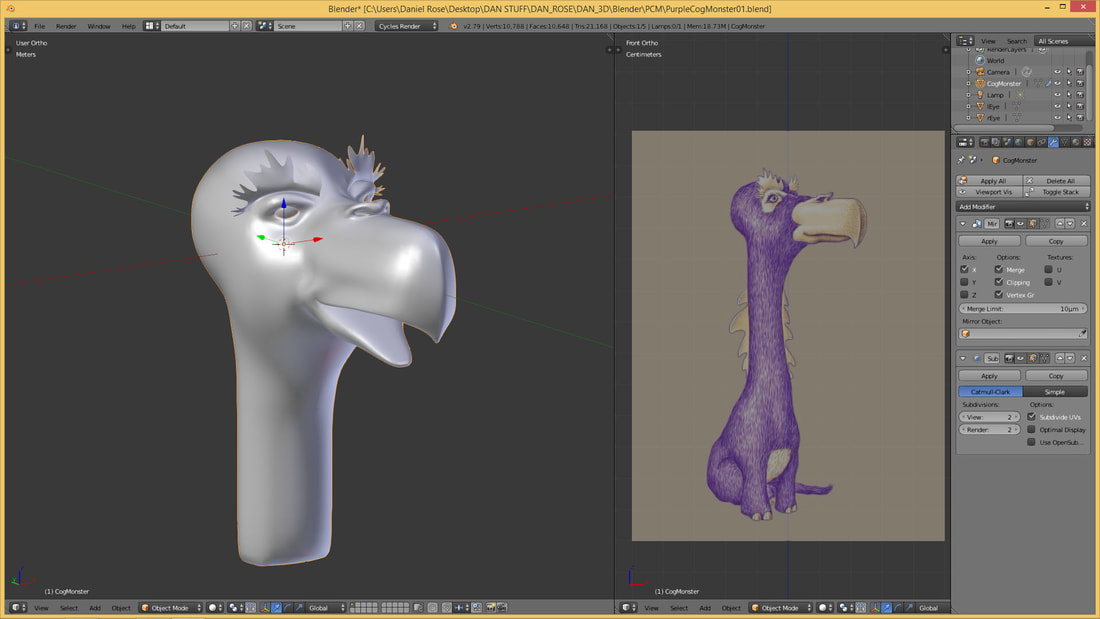

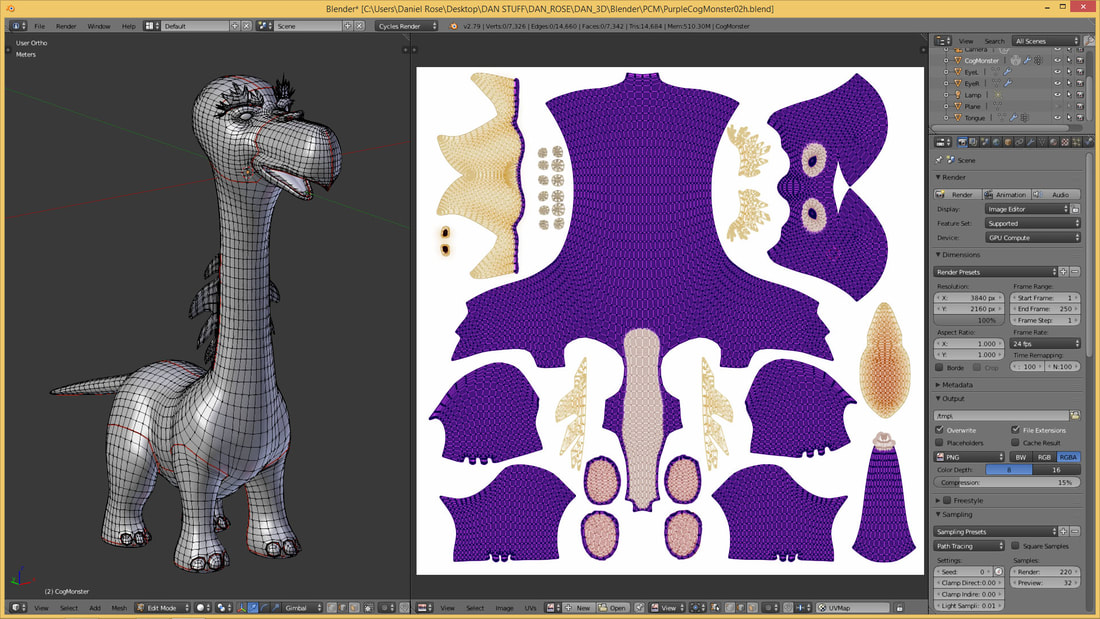

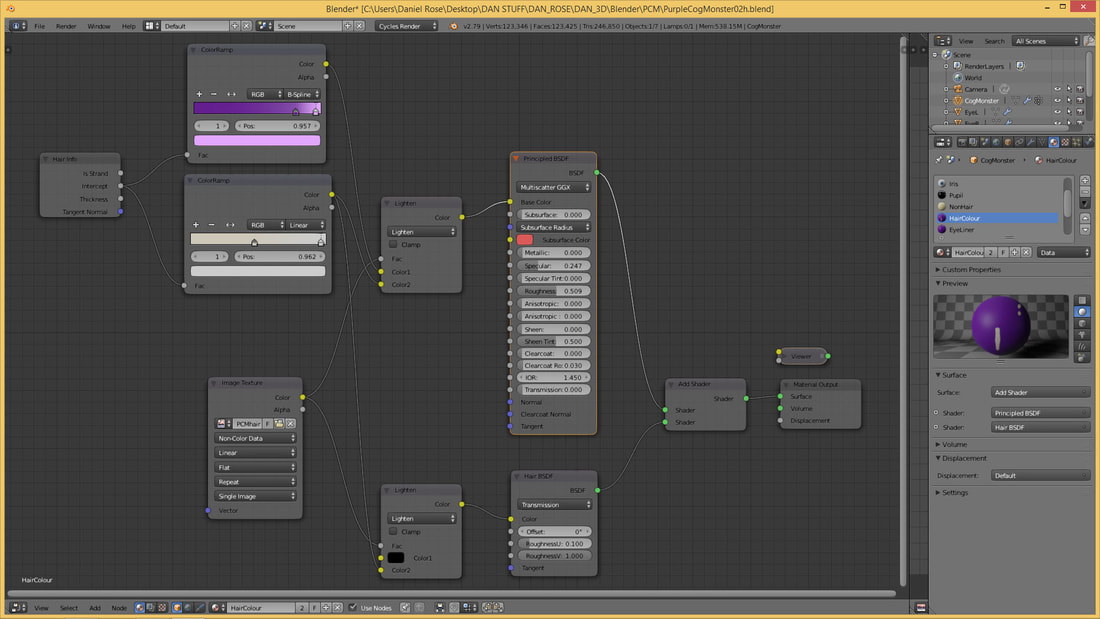

As part of my ongoing transition to Blender for my 3D modelling and rendering services I've been busy creating a little character called the Purple Cog Monster. He's the mascot for my partners company PCMcreative. I've just completed the modelling and texturing phase, but eventually he'll be animated. Computer 3D (like most other art forms) is a never-ending learning process. There are so many areas of specialism in computer 3D that any given individual can only dream of mastering them all. There are experts in modelling, UV unwrapping and texturing, materials creation, lighting and rendering. Specialisms include character creation, environment design, dynamic simulation, particle systems and physics, rigging for animation - it's endless. Then there's 3D for image rendering, for animation, games and virtual reality, for augmented reality. Each has it's own complexities and work-flows. I'm humbled every day as I learn something new. Somewhere in England there is a wall in a house... It was a party of sorts, hosted by my sister more years ago than I care to remember, just prior to a major re-decoration of the house she lived in at the time. 'Just draw or write what you like, have fun'. So we did, and by the end of the evening the walls were covered from floor to ceiling with everything from poetry to satirical and surreal drawings - it was here that the Purple Cog Monster was born. My partner sort of fell in love with him, gave him his name and gradually adopted him as mascot for her business. He's been with us ever since. Some Years Later... I'd done a few drawings of the PCM over the years, and even attempted a 3D version in Poser 3D (character creation software) which faltered at an early stage. It was only recently as I was getting fully into Blender that I decided to do the job properly. Modelling The Image above shows the early stages of modelling the PCM. It's probably the most important process to get right as just about everything that follows interacts with the mesh you create in some way or another - how light will reveal its form, how difficult it will be to texture and rig for animation etc. I tried for a fairly low-poly figure mesh (useful for lowering render times and easing other aspects of the creation process). I also decided not to be too rigid in my approach to interpreting the initial character references - I wanted to create perhaps a more 'cute' version than the original. Subdivision Surface, a modifier added to increase the complexity of base geometry without destroying the simpler mesh, helps smooth and refine its form. I took my time over the modelling process, taking about 2 days to create and refine the shapes until I arrived at the mesh in the images below. UV Mapping Then I moved onto UV mapping the model. UV mapping is the process of 'unwrapping' the model in order to apply the flat image textures that would help give him his colouration and some extra detail. You have to think of this process as if you were a tailor preparing shapes of material to 'clothe' the model in colour Texturing Once unwrapped you can export the flattened shapes to be used as guides to paint the colour in an image editor. This is a complex process in itself, which can also be done in the 3D software directly onto the model in the viewport. But in this instance I did most of the work in Photoshop as there were very few areas where detail would cross the seams of the UV shapes and so would not be visible when applied to the model. Hair I knew early on that I wanted to use Blenders hair tools to give the PCM a proper pelt of simulated fur that had dimension. You can use image textures to give the surface of a 3D model the appearance of having hair, but it always has a somewhat flat look. In Blender hair is simulated by using Particle Systems, modifiers that distribute simple geometry or effects over the base mesh. I'd used a very similar (but simpler system) in Poser 3D but it used to take an incredibly long time to render and styling the hair was next to impossible. By contrast Blender hair can be optimised to render very quickly (useful when rendering hundreds of frames for an animation) and styling is really very simple. You can comb hairs to flow in the directions you choose, lengthen or cut the strands and even run dynamic simulations with real-world physics parameters. The settings available are frightening. I spent a good few days getting the look I really wanted (I wanted a slightly matted carpet in appearance), re-styling and test rendering many iterations to see how it all worked. Materials Blenders Cycles rendering engine, the power-house behind getting a good image of your 3D models and scenes, uses a node-based materials system. All manner of dialogue boxes that define various aspects of the way you want your materials to look all joined together with spaghetti.

There are basic parameters for defining simple attributes like colour and how shiny a surface is, inputs for using texture maps, specific nodes for hair. Then there are mathematical nodes that modify and combine other inputs together to arrive at the final material that the render engine uses to interact with scene lights and camera values & movements. The complexity is dizzying. The material you see here was for the hair, and it's actually a very simple set-up. I've seen node set-ups that scroll across several pages with scores of nodes. But there's more to do... So that's where I am at the time of writing this post. I have a UVmapped 3D model with hair and materials applied that renders...not too badly. But I intend for the PCM to be animated, and that means I have to enter the realm of rigging him to be able to walk and move his head, blink and open his mouth. And then I have to become an animator. There's a lot to do. Cheers for now, Dan

1 Comment

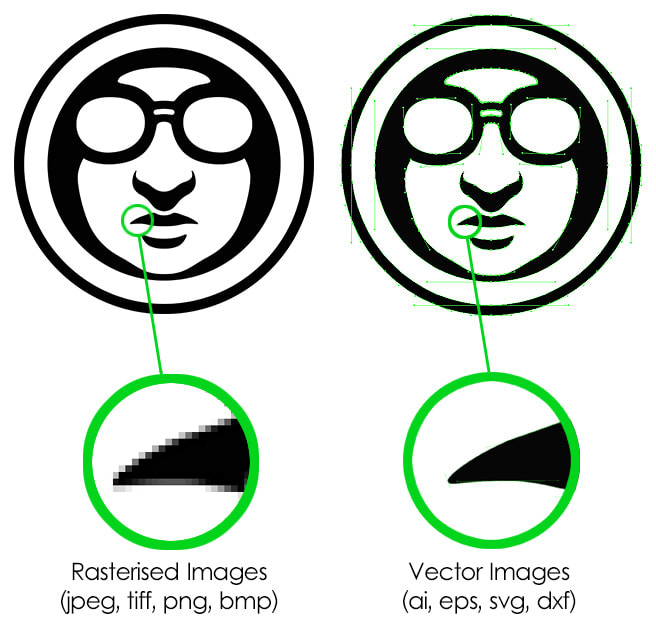

There are two basic types of computer generated images, Raster and Vector. Raster Images By far the most common type are Raster images (or bitmaps) and will be familiar to you as digital photos on your phone or computer as well as the majority of graphics used on your web presences. They are also widely used in print media and promotional materials. The most common raster image file formats are jpg (or jpeg), gif, png, tiff and bmp. Raster images consist of pixels (tiny squares of colour) layed out in a grid that combine to make up the entire picture. The higher the number of pixels in the grid the more detailed the image will be. This is usually referred to as the resolution of the image and often measured in dots-per-inch or dpi. Vector images Less familiar outside graphic art-working professions, vector graphics are fundamental for a range of applications that are expanding as technologies develop. Used for some time by graphic designers and digital art-workers to create logos and other promotional graphics, they also form the basis of CAD (computer aided design) software and can be used to drive many modern machine operations that require tools to follow pre-defined paths. They are also used in computer 3D processes and even the very text I'm typing with now. Common vector files are ai, eps, svg and dxf. Vectors are so powerful because they use mathematical calculations to define how points (or vectors) are joined together to create shapes. Vectors can be joined by straight lines or by curves, and the shapes made from these lines can be filled with colour or given a line thickness among other properties. They tend to have smaller file sizes than raster images. Scalability The mathematical nature of vector graphics give them a number of advantages over their raster counterparts. Unlike raster images vectors can be scaled without losing any quality - if you try to increase the size of a raster image (even with re-sampling algorithms) you're really just enlarging the pixels you started with, meaning you end up seeing square-edged lines or 'jaggies' (see top image). With vectors everything remains crisp and sharp however large you print. Over the years I've done a fair few projects converting clients' raster logos into vector formats so that they can be printed as large scale signage. Versatility One of the other advantages of vectors is that they can be used in all kinds of other digital applications like computer 3D. You can take vector shapes and use them to make objects applying all kinds of materials and lighting effects, and even make nice animations to wow your clients. 3D CAD files used by engineers, designers and architects also use the power of vectors and can easily be exported to other applications to create beautiful photo-realistic renders. The use of vector artwork in computer aided machine cutting operations has become quite commonplace over the past few years, although you might not have realised it. Those little wooden key-rings in a myriad different shapes (often with black edges) are a classic example. I've prepared vectors for a great many projects including large layered sculptural relief artwork, all made possible using this digital drawing technique. I've also used vectors to make custom shaped frames for paintings that strayed from the classic rectangular proportions. So as a final comment, for scalable graphics with great versatility and functionality in the age of computer technology, vectors are the thing. All hail the vectors!

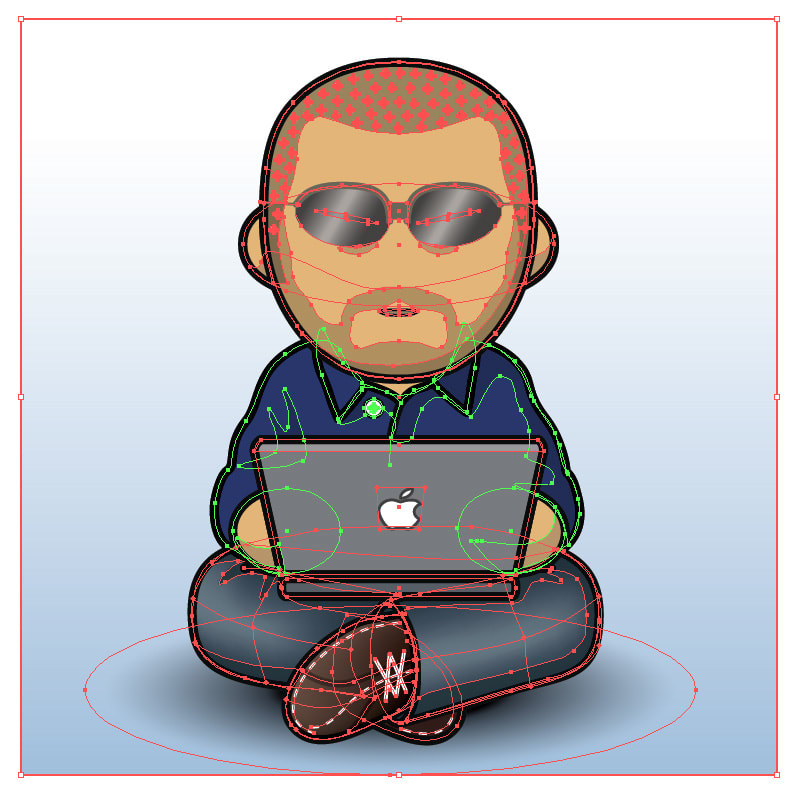

Visual Ratio is the new face of the digital art services I've been providing to clients for some years now. I realised I needed to draw a distinction between these computer-based visualisation skills and those of the traditional painting work that I still do from time-to-time commercially (but far less frequently now). The focus of Visual Ratio is to bring visualisation services to innovators, entrepreneurs, designers, inventors and businesses across a broad spectrum. This includes creating and rendering digital 3D models to illustrate and contextualise new ideas and products before they go to manufacturing. This can be incredibly informative to the design process and also form the basis of marketing and information materials. Computer 3D will provide much of the content for up-coming technologies such as 3D printing, augmented reality and virtual reality, which will become much more familiar in the years to come. The digital tools and skills developed over my commercial career also provide scope to offer a range of extended services, including branding such as logos, digital image editing for web design, and vector artwork for CNC machine cutting. So I've been spending a lot of time developing the new website and getting processes into shape. I've also been transitioning onto a different computer 3D platform (Blender 3D) which offers a more comprehensive set of tools for modelling and rendering than I've been able to access up to now. I really like the enhanced photo-real renders I've been able to make so far and it'll only get better. The anvil model is from a tutorial I've been following to get right under the hood of how it all works. I love the new materials I've been able to create with the principled shader-system in Blender and the lighting is amazing.

All in all I'm feeling set for up-coming projects! Dan |

AuthorDaniel Rose is a UK digital creator and artist, working commercially for over 20 years. ArchivesCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed